but in the depth of reflection I found here, there are perhaps few better ways to remember those who served.

A couple months ago, I actually took a holiday. I went at the end of January, looking for a break from the Ohio winter that wasn’t overrun with spring-breakers. The destination had to check a few boxes: it couldn’t look like Anytown, USA, the food had to be great (I’m a fat guy— I have my priorities), and I wanted a place with a culture rich in history. New Orleans— “NOLA” for the initiated— was the perfect choice.

It’s hard not to talk about the music, the food, the art, the people… but I’m going to focus on one experience that left me stunned: my visit to The National WWII Museum.

There’s no burying the lede: The National WWII Museum is a treasure cove of stories, artifacts, reflection, grief, and trauma. WWII is the worst thing humanity has ever done— whether the atrocities that started it or the horrific lengths required to end it— and this museum in New Orleans covers every angle.

The first thing that left me astonished was the scale. Think of the largest museum you’ve been to. Now double that, raise the ceiling by 100 feet, and you’re still only imagining a fraction of it. And that’s just one of five buildings. I spent six hours there, didn’t break for lunch, rushed through parts toward the end, and still missed an exhibit.

And the scale isn’t just physical—it’s emotional. It’s in every story.

You start off on a train that introduces you to the world you’re about to explore, and you’re given a dog tag representing a real person who served in WWII. Mine belonged to Joe Crane. I won’t try to summarize his story— it deserves better than a paragraph— but here’s what stuck with me: he enlisted after Pearl Harbor. He was part of the invasion of Sicily. He piloted a landing craft to shore at Omaha Beach on D-Day.

. . . He was a 15 year old kid.

I followed his story throughout the museum, unlocking videos and details at each exhibit. Joe wasn’t just a fact on a placard— he was someone I traveled with.

And Joe’s story was just one among thousands. The museum brings the era to life, not just with artifacts, but with experience.

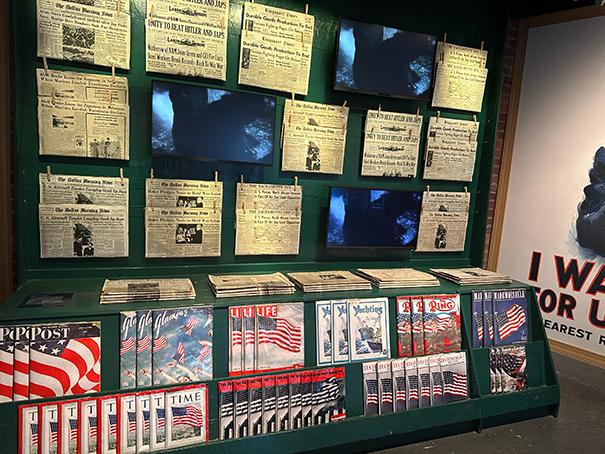

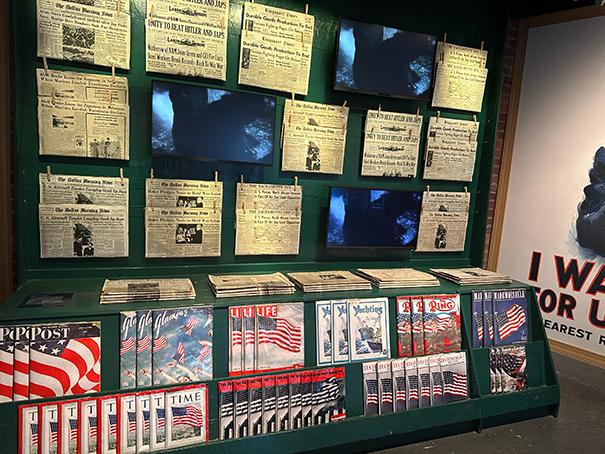

Walk through a wartime American home. Glance at a newsstand filled with real magazines and newspapers from the era. I stood in front of a real movie theater facade, exactly like the ones that would’ve played wartime reels, with exactly the same posters, watching exactly the same propaganda movies. I lingered there— knowing what cinema was then: not escape, but persuasion, rallying, resolve.

I turned a corner and found myself in a jungle, marching toward a howitzer while the sounds of distant gunfire cracked around me. It was unnerving. It was meant to be.

Executive Order 8802, which opened jobs to Black Americans. “No surrender” Japanese propaganda that only just begins to explain why the atomic bomb was seen as necessary. Then you enter a full Japanese American internment camp reminding you of the conditions we put them through while they still played a vital role in the war efforts.

There’s a clear and intentional spotlight on the roles women played— in the household, in the factories, and in uniform: as WASPs, nurses, and codebreakers. Half a million Latino or Hispanic Americans served in the military. Ira Hayes was one of 45,000 Native Americans who served. In some tribes, 70% of the men were in the military— Native Americans had the war’s highest rate of volunteers.

Many— if not most— of the individuals within these groups faced racial violence, hatred, and were treated as disposable. These were people fighting for the same cause, against the same injustice, claiming the same freedoms— yet met with the same hate they were being sent overseas to defeat. And still, they chose to serve— fighting two wars at once.

One of the most sobering moments came when I saw a small section on the Bataan Death March. I grew up in Port Clinton, Ohio— a small town of fewer than 2,000 people. We sent 42 soldiers to the Pacific. 32 of them were captured. Only 10 came home.

And then Anne Frank’s house. Followed by the quarters where Jewish prisoners were kept until . . . it was just a long day . . .

Just a few hours of learning about it, and it was hard. That’s the point, though— I think.

Memorial Day! BBQs! Amusement Parks! Kickoff to summer! We’re supposed to enjoy the weekend, but we’re also supposed to pause for a moment— to reflect.

WWII is the worst thing humanity has ever done.

And the only thing that could ever be worse… is if we repeat it.

Hatred brings with it a terrible cost.

And far too often, we’re left with nothing but memories for those who fought it.

And the only thing that could ever be worse… is if we repeat it.

Hatred brings with it a terrible cost.

And far too often, we’re left with nothing but memories for those who fought it.

We'd Love to Hear from You

Whether you're curious about product features, a free sample, or need to know if we have a material in stock— we're ready to answer any and all questions.